Maria Sofia Emma Piacentina de Arsena Eisner is known to her 11 children and 34 grandchildren as Sofia. She doesn’t quite reach five feet tall, she’s quietly perched in an orange chair, rounded against the curvature of her spine.

It’s not her house, but it could be. Pictures of her are scattered around it, some with her hair long and brown, then short, now silver and wiry framing her face. There’s one photo on a yellow-tinted wall behind her. She’s standing tall with her late husband, Peter, as he fishes with one of their sons and a few of his children, their grandchildren. It’s about a decade old by its fray and color.

Sofia looks as at home as ever in the house of her oldest son, Jorge, in Chaleco, just outside the city limits of Buenos Aires. It’s picturesque. As she talks, she looks at the long pool through the tall window, teeming green grass and the tiniest breeze surrounding her, drifting into the house. She remembers the birth of all 11 of her children, meeting her 34 grandchildren (split right down the middle, 17 girls and 17 boys).

She scoffs and describes herself as “nothing,” while blowing a raspberry and looking off into the lush bushes bordering the pool. Not Argentine, not Italian, not one, not the other —but she’s the opposite of nothing.

She’s a mother, deeply grounded in a sense of home and memory. Not home as a place, but the type of home you might find in others, in family. You can see it in her face, the way it softens when she mentions the name of one of her kids or grandkids.

Jorge’s story is somewhat of a mirror to his mother’s—he grew up in European schools and ended up pursuing a graduate degree in the United States. And Sofia’s story is a common narrative: European immigration to Argentina during the 20th century.

Sofia’s parents were born in Italy and moved to Argentina just two years before she was born. She speaks Italian, but also Spanish. She switches between Italian, French, Spanish and English and asks her son to explain little words and turns of phrase for her.

She has lived in Buenos Aires for all 88 years of her life; she’s raised her children here, sent them to schools and watched them move to other countries. Her family has splintered.

Her children and her children’s children have left home and come back. But when they do return, another leaves. The grass is overgrown in her lofty home that once housed all of her children, sometimes four to a room.

Family is still everything. She has plans to visit her son Pablo’s children in Texas soon and attend a bar mitzvah. Sitting in her chair, she declined calls, hushing her children and grandchildren away, shaking her hands at her phone, like she was in the same room as them.

“We have very large phone bills,” Jorge said. “She doesn't use WhatsApp, she doesn't use the new technology. She talks with everybody lots of times, if they cannot come here. Some come here more than others.”

Still, they are constantly apart, and Sofia is relentlessly independent. The big, Italian families that she remembers from her adolescence in Buenos Aires are splintering—because of distrust in the economy, because of growing opportunity overseas, and because of simple wanderlust. Her children are doctors, geologists, engineers and more.

Sofia’s family is by no means an anomaly. It’s become a tradition of sorts for Argentines, especially those with European ancestry, to become displaced and scattered throughout the world in search of opportunity outside of their home country’s economic instability and high inflation rates. Even with a new government and some cuts to spending and privatization of national resources, Argentines are beginning to hope for better days while simultaneously holding their breath that stability may not come permanently, as crises of economy have repeated themselves time and time again.

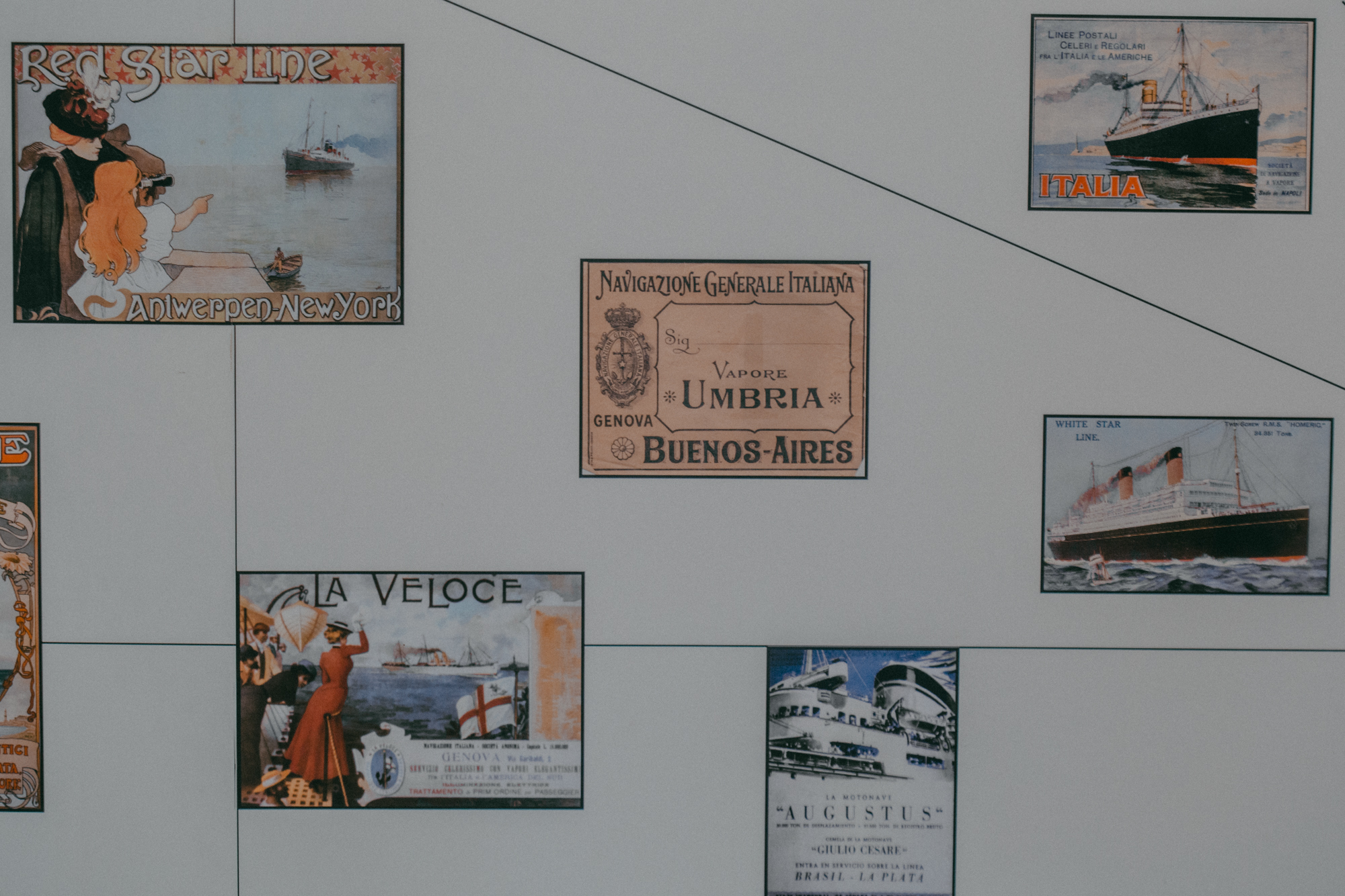

NATION OF MIGRANTS

Sofia stayed in Argentina because her husband’s business was there. She lived through La Guerra Sucia, “The Dirty War,” and the presidencies of Perón, Macri, and now Milei. None of it fazes her anymore.

“Argentina is phenomenal, but it's so very criticized,” she said. “If we have Milei, bye Milei, if we have Perón, well, of course, Perón was horrible.”

Sofia taught all her children Italian.Her son Jorge said it was natural that the language was passed through his mother. When Sofia married her late husband, he had to learn it too. .

Italy has left an indelible footprint on Argentinian culture. One of the country’s most notable figures, former president and dictator Juan Perón, was of Italian ancestry. Argentina has been labeled a “crisol de razas,” or “crucible of races,” due to the diverse ethnic makeup , including Europeans, Indigenous communities and immigrants from neighboring Latin American countries. But Argentina remains overwhelmingly European.

Sofia was born into a nation of immigrants—people from Spain, Italy and other western European countries came to Argentina after the First and Second World Wars. According to the 1914 census, 30 percent of the population was foreign-born, a number that continues to rise. . Between the 1850s and 1950s, 3.5 million Italians immigrated to Argentina. Today, 62 percent of Argentina’s population is of Italian ancestry. Italian is the second most spoken language in the country after Spanish.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Argentina faced a military dictatorship known as the Dirty War. During this time, millions were kidnapped, murdered or forcibly disappeared by the government. Militia groups would often impersonate military officers to stop, detain, and kidnap Argentines on the street. According to the Archives of Terror, a collection of materials piecing together the narratives of the era’s abuse, 30,000 individuals disappeared, while thousands more murdered or imprisoned.

Sofia remembers her husband telling her about the time he was almost kidnapped by men dressed as military officers. And once, Jorge left rugby practice at his school one day and was stopped by military officers asking for his documents. He didn’t have any and explained that he had been on a long run that day and was let go. Still, he wonders what would have happened if they hadn’t let him go, if they were military officers, if he could have become one of the disappeared.

The majority of these disappearances were carried out by government actors, such as the Secretaría de Inteligencia del Estado (SIDE), but some were disappeared by guerrilla groups, such as the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, known casually as the Triple A.

“We have this theory of the two demons,” Jorge said. “The military was one of the demons, but the terrorists were the other demons.”

Current President Javier Milei has denied the number of people who disappeared during the junta dictatorship, placing blame on leftist or Perónist military groups instead. In his election victory speech in 2023, he said, “There were no 30,000.” Many proponents of denialism in Argentina claim that leftist terrorists and guerrilla groups caused a higher number of these disappearances.

As Argentina Shifts, Families Scatter: A Story of Home and Migration

FUERA MILEI

The Argentine economy has been in a flux marked by inflation for decades. The IMF and Forbes Magazine have declared Argentina as the country with the most inflation in the world—especially after the country’s 2001 financial crisis. This cyclical pattern has led many Argentines towards fleeing the country — either on foot or with their passports, as they seek citizenship elsewhere through work,

President Milei received Italian citizenship through his grandparents’ heritage this year. Many others have preceded and succeeded him in doing the same. Argentinians are seeking dual citizenship in high numbers, because of a decades-long distrust in the country’s economy and its inflation crisis. Even Milei sought Italian citizenship through his grandparents’ ancestry last year.

Prices were different every day, but Milei, a self-proclaimed “anarcho-capitalist,” claims to have calmed the market, with inflation hitting a five-year low. This February, the inflation rate was 2.4 percent. His policies are perplexing, some in line with the populist right leaders of Hungary and Turkey in Central Europe and President Donald Trump in the U.S.

He is also committed to deregulation.. Like Trump, he’s introduced executive policies that weaken the government’s reach. He wants to take a “chainsaw” to bureaucracy, and has built up relationships with nationalist leaders, like Trump.

The IMF projects Argentina's real GDP growth at 5 percent for 2025, according to their website. His administration has also secured congressional approval to negotiate a new loan with the IMF, aiming to strengthen the country's financial reserves and address currency challenges.

Milei, who was recently indicted in a cryptocurrency scam, has ignited large-scale pushback from Argentinians about his social policies and rollbacks of social security programs. Streets in Buenos Aires’ Congreso neighborhood, the governmental center of the city, are often laden with the words “Fuera Milei” or “Out Milei”.

Young, progressive Argentines, many of them women, want him and his social policies gone. Some of them have left because of it.

Clara Bofelli is from Patagonia, the mountainous glacier region in southern Argentina. She moved to Buenos Aires in her early 20s, living somewhat of a Bohemian lifestyle, working at a migration organization that helped migrants from Venezuela.

She didn’t stay and moved to Colombia early last year because of a myriad of reasons—but primarily because of her frustration with the new Argentina government.

"It’s becoming less desirable under Milei’s policies,” she said.

Milei has likened himself to a man with a chainsaw, ripping through bureaucratic systems that have cost the national economy. He even gave a chainsaw to Elon Musk at the conservative CPAC convention in the U.S. where Musk brandished the saw. Still, young Argentines like Mariana Vaccarro are leaving en masse, in search of professional opportunities with higher earning potential, or out of frustration with Milei’s governing practices.

Vaccarro is a podcast producer from Buenos Aires, she recently moved to Madrid because she wasn’t getting paid enough, especially in comparison to her coworkers in Spain and the U.S. She wants to return home, but she said she wants to make more money before she does.

Young professionals leaving Argentina has been casually labelled a “brain drain.” The American Association for the Advancement of Science reports that since Milei has taken office, Argentina’s main scientific agency lost nine percent of its employees. Vaccarro and Boffelli echo that this is true for other industries too.

BROKEN FAMILIES

Argentines were leaving decades before Milei, too. In the early 2000s, when Argentina was experiencing an economic crisis, Sofia’s son, Jorge, left Buenos Aires to pursue a Master of Business Administration in the United States at Purdue University. He returned to Argentina a few years later and began working at Shell Inc., where he ended up introducing the concept of convenience stores to the country. His children were born and raised here. But he remembers Perón’s1990s and coming back to inflation that was worse than ever.

“Inflation especially hits the people who don't have the opportunity to save or to transform what they get into dollars,” he said.

When he returned, he came back to his mother.

While some, especially proponents of Milei, say that the Argentine economy is better than ever before, it’s still unlikely for those who have moved away to return. The country experienced three hyperinflations during the 20th century and had the highest inflation rate in the world in 2023. This crisis is by no means finite.

Sofia’s granddaughter, who bears her name, wants to leave and isn’t thinking twice about it. She’s planning to move to Spain and says it won’t splinter any of her familial bonds because of the number of family members who have chosen to leave before her.

As his mother talks, Jorge’s eyebrows bunch up and raise, following his mother’s utterance of every word. He follows her, but she only follows herself—a matriarch to her core. Jorge visits with his mother and drives her around, her sitting in the back of his tiny black car.

His eyes are kind, too. Fatherhood isn’t a vocation for him—he would be with his children, who are spread out across continents, every waking moment if he could. Like mother, like son. He said he tries to push his sons to leave, to open their minds, to have international experiences.

“I feel as if I belong here when I think about Argentina,” Jorge said. But he wants his children to be able to leave, and he’s happy to see them grow. Perhaps he learned it from his mother.

A few years ago, Sofia went to visit her son, Ernesto, in New York City. They gave her a pink mug, laden with the phrase, Mom-ming ain’t easy.

“It's true, ‘momming’ ain't easy,” she said. Especially in Argentina, especially for her.

Sofia stays seated in her little chair. She isn’t worried about herself, but about “that one,” she says, pointing at Jorge. Most days, she reads and keeps her house in shape. She doesn’t tend to her garden anymore, though she used to.

Jorge looks on at her as she talks. She says softly, “I would like to die in peace, I would like to die in a very normal way.”